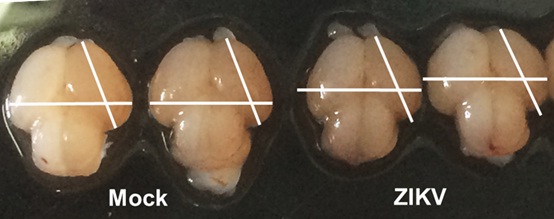

Mouse fetuses injected with the Asian Zika virus strain and carried to term within their pregnant mothers display the characteristic features of microcephaly, researchers in China report May 11 in

Cell Stem Cell. As expected, the virus infected the neural progenitor cells, and infected brains reveal expression of genes related to viral entry, altered immune response, and cell death. The authors say this is direct evidence that Zika infection causes microcephaly in a mammalian animal model.

The research was a collaborative effort between XU Zhiheng at the Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and QIN Cheng-Feng at the Beijing Institute of Microbiology and Epidemiology.

“The most surprising part of this study is that it was mostly neural progenitor cells that got infected in the beginning and mostly neurons that became infected at a later stage - 5 days after injection when the presence of Zika virus increases several hundred folds.” says co-senior author XU. “However, almost all cell death was found in neurons other than neural progenitor cells. This indicates that neurons, but not neural progenitor cells, are prone to induced cell death by the Zika virus.”

Zika virus was injected directly into fetal mouse brains. If given too early the embryos didn’t survive, so the researchers began by looking at the equivalent of the second trimester in humans, when the fetus’s neural progenitor cells are intensively expanding and generating new neurons at the same. With this model, they could observe as the brain shrunk with the increase in viral load combined with the intense immune response.

The mice survived to birth but were eaten by their mothers, which often occurs if pups are noticeably unwell, preventing further observation. To overcome this problem, the researchers plan to use lower doses of the Zika virus to see if that will affect survival. The researchers are also working to identify potential drugs that could reverse the process of Zika virus-induced microcephaly in mice.

“Mice are not humans, and we need be careful when translating our findings into human disease,” says QIN, the other co-senior author on the paper. “Extensive experimental and clinical investigations are urgently needed in response to this global crisis.”

“Our animal model, together with the global transcriptome datasets of infected brains, will provide valuable resources for further investigation of the underlying cellular and molecular mechanisms and management of Zika virus-related pathological effects during neural development,” XU says.

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China and Ministry of Science and Technology of China.

Brains of smaller sizes compared to those of their mock infected littermates were detected after ZIKV infection. (Image by LI Cui, et al.)

Author Contacts:

zhxu@genetics.ac.cn QIN Cheng-Feng, Ph.D.

Department of Virology, Beijing Institute of Microbiology and Epidemiology

Brains of smaller sizes compared to those of their mock infected littermates were detected after ZIKV infection. (Image by LI Cui, et al.)Author Contacts:zhxu@genetics.ac.cn

Brains of smaller sizes compared to those of their mock infected littermates were detected after ZIKV infection. (Image by LI Cui, et al.)Author Contacts:zhxu@genetics.ac.cn CAS

CAS

中文

中文

.png)