Wheat, which includes bread wheat and its relatives, is a staple food crop that feeds about 35% of the world’s population. As one of the first ancient crops to appear in the Fertile Crescent, wheat has been cultivated for over 10,000 years since the “Neolithic Revolution” and is considered a transformative force in human society. Despite its economic importance and intimate bond with humanity, however, the population history of wheat is still unclear.

In a new study published in Nature Plants, researchers led by LU Fei from the Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) have uncovered the evolutionary history of wheat during the Holocene.

In this study, ZHAO Xuebo, GUO Yafei and their colleagues in LU’s group collected whole-genome sequences of 795 wheat accessions from six species and 25 subspecies in the genera Triticum and Aegilops (wheat). They then constructed a genus-level genetic variation map of wheat (VMap 1.1) with about 78 million single-nucleotide polymorphisms.

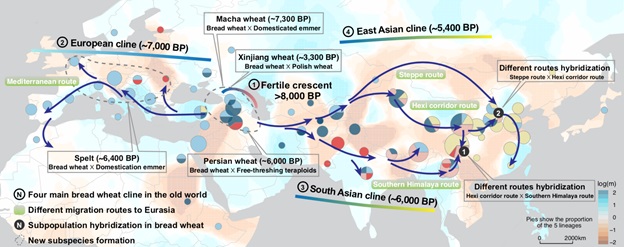

Using demographic modeling of the genomic data, the researchers found that bread wheat originated from a polyploidization event near the southwest coast of the Caspian Sea. However, continued gene flow from its relatives resulted in a slow speciation process of bread wheat that lasted about 3,000 years. Bread wheat then rapidly spread across Eurasia, reaching Europe, South Asia, and East Asia between about 7,000 and 5,000 years ago (Fig 1).

Fig 1. Trans-Eurasian expansion of bread wheat (Image by IGDB)

The trans-Eurasian dispersal shaped a generally diverse but occasionally convergent bread wheat adaption landscape: The researchers found that three independent loss-of-function mutations in a prime flowering time gene (Ppd-D1), conferring early flowering phenotypes, helped bread wheat adapt to Europe, East Asia and South Asia, respectively.

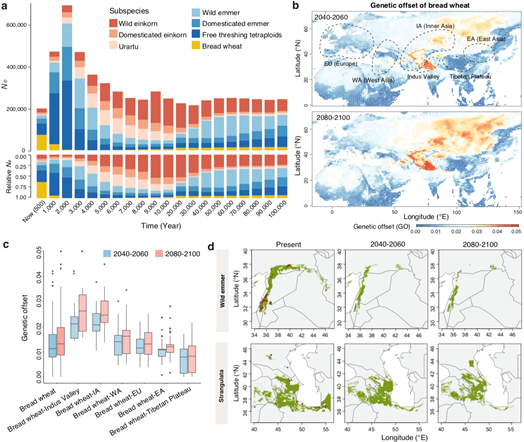

Crop relatives are valuable for breeding resilient crops in a changing climate. However, the researchers identified a worrying decline in the population size of some of bread wheat’s most critical relatives due to changes in human diets and vulnerability to future climate change (Fig 2). For example, the population size of diploids and tetraploids in Triticum has declined by 82% over the last 2,000 years. This finding highlights the urgent need to protect and conserve wheat biodiversity.

Fig 2. The population size fluctuation of wheat from the past to the future (Image by IGDB)

In conclusion, this study provides a comprehensive set of demographic models that unravel the population history of bread wheat and its relatives and has paved the way for the effective dissection of the genetic mechanisms of wheat adaptation.

These findings are expected to support informed efforts to conserve wheat biodiversity and breed climate-resilient crops in the future.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the Strategic Priority Research Program of CAS, the National Key Research and Development Program of China, and the Hainan Yazhou Bay Seed Lab.

Contact:

Dr. LU Fei

Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences

Fig 1. Trans-Eurasian expansion of bread wheat (Image by IGDB)The trans-Eurasian dispersal shaped a generally diverse but occasionally convergent bread wheat adaption landscape: The researchers found that three independent loss-of-function mutations in a prime flowering time gene (Ppd-D1), conferring early flowering phenotypes, helped bread wheat adapt to Europe, East Asia and South Asia, respectively.Crop relatives are valuable for breeding resilient crops in a changing climate. However, the researchers identified a worrying decline in the population size of some of bread wheat’s most critical relatives due to changes in human diets and vulnerability to future climate change (Fig 2). For example, the population size of diploids and tetraploids in Triticum has declined by 82% over the last 2,000 years. This finding highlights the urgent need to protect and conserve wheat biodiversity.

Fig 1. Trans-Eurasian expansion of bread wheat (Image by IGDB)The trans-Eurasian dispersal shaped a generally diverse but occasionally convergent bread wheat adaption landscape: The researchers found that three independent loss-of-function mutations in a prime flowering time gene (Ppd-D1), conferring early flowering phenotypes, helped bread wheat adapt to Europe, East Asia and South Asia, respectively.Crop relatives are valuable for breeding resilient crops in a changing climate. However, the researchers identified a worrying decline in the population size of some of bread wheat’s most critical relatives due to changes in human diets and vulnerability to future climate change (Fig 2). For example, the population size of diploids and tetraploids in Triticum has declined by 82% over the last 2,000 years. This finding highlights the urgent need to protect and conserve wheat biodiversity. Fig 2. The population size fluctuation of wheat from the past to the future (Image by IGDB)In conclusion, this study provides a comprehensive set of demographic models that unravel the population history of bread wheat and its relatives and has paved the way for the effective dissection of the genetic mechanisms of wheat adaptation.These findings are expected to support informed efforts to conserve wheat biodiversity and breed climate-resilient crops in the future.This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the Strategic Priority Research Program of CAS, the National Key Research and Development Program of China, and the Hainan Yazhou Bay Seed Lab.Contact:Dr. LU FeiInstitute of Genetics and Developmental Biology, Chinese Academy of SciencesEmail: flu@genetics.ac.cn

Fig 2. The population size fluctuation of wheat from the past to the future (Image by IGDB)In conclusion, this study provides a comprehensive set of demographic models that unravel the population history of bread wheat and its relatives and has paved the way for the effective dissection of the genetic mechanisms of wheat adaptation.These findings are expected to support informed efforts to conserve wheat biodiversity and breed climate-resilient crops in the future.This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the Strategic Priority Research Program of CAS, the National Key Research and Development Program of China, and the Hainan Yazhou Bay Seed Lab.Contact:Dr. LU FeiInstitute of Genetics and Developmental Biology, Chinese Academy of SciencesEmail: flu@genetics.ac.cn CAS

CAS

中文

中文

.png)