Researchers have decoded a long-standing mystery of how flowering plants ensure their sperm cells successfully reach the egg for fertilization, according to a recent study published in the journal of the Nature Plants (10.1038/s41477-025-02084-9).

Unlike animals, where sperm swim actively, plants rely on a delicate transport system inside pollen tubes to deliver immotile sperm. The key lies in a structure called the male germ unit (MGU)—a tiny cellular package that carries both sperm and a companion nucleus through the pollen tube.

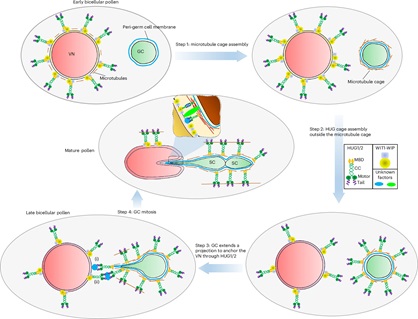

The study, led by teams of Prof. YANG Weicai and Prof. LI Hongju from the Chinese Academy of Sciences identifies two motor proteins, HUG1 and HUG2, form a kinesin cage encasing a microtubule cage around the generative cell or sperm cells and vegetative nucleus that act like molecular arms, to link them together during pollen development. Without these “hugging” proteins, the sperm cells get left behind, leading to complete plant sterility.

“It’s like a cellular carpool system,” explains Dr. CHANG Shu, one of the authors. “The HUG proteins make sure everyone gets in the same vehicle and arrives together at the destination.”

Using advanced microscopy, the team observed that HUG proteins form a cage-like structure around the sperm cells, anchored by a microtubule cage network. This “kinesin cage” ensures the generative cell (the precursor cell of the two sperm cells) physically anchors to the vegetative cell nucleus through extending a long tail, forming the male germ unit, in bicellular pollen. With this unit, the sperm cells are transported within the growing pollen tube into the embryo sac for double fertilization, which produces the embryo and endosperm in seeds.

The findings not only solve a 40-year-old biological puzzle but also open new avenues for improving crop breeding and seed production. Understanding how sperm delivery works—and why it sometimes fails—could help scientists enhance fertility in economically important plants, especially under environmental stresses which often disrupt sperm delivery.

“This finding illustrates that the HUG-mediated establishment of the MGU is an extremely sophisticated and complex process, which is fundamentally important for double fertilization.” said

Prof. LI Hongju.

Working model of HUGs in MGU organization. (Imaged by Chang et al.)

Contact:

Prof. LI Hongju

Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences

Email: hjli@genetics.ac.cn

Working model of HUGs in MGU organization. (Imaged by Chang et al.)Contact:Prof. LI HongjuInstitute of Genetics and Developmental Biology, Chinese Academy of SciencesEmail: hjli@genetics.ac.cn

Working model of HUGs in MGU organization. (Imaged by Chang et al.)Contact:Prof. LI HongjuInstitute of Genetics and Developmental Biology, Chinese Academy of SciencesEmail: hjli@genetics.ac.cn CAS

CAS

中文

中文

.png)